The best Baja road trip: A drive down Highway 1 in Mexico

The highway forward stretches 1,063 miles, starting on the Mexican border. Outdoors your automobile window, you see the cactus-and-boulder expanses of Joshua Tree — however with seashores. Or perhaps it’s the Outback of Australia, with taquerias.

It’s the Baja peninsula’s Freeway 1 that I’m speaking about. For eight days this winter — simply earlier than the newest burst of cartel violence claimed three lives on Mexico’s east coast — I adopted the highway from the border to its rocky conclusion in Cabo San Lucas. The journey included six-fingered giants, child whales, tropical fish, dry lakes, half-forgotten missions, sons of pioneers, yacht folks, panga folks, tricked-out vans and tenacious cyclists.

I used to be on the lookout for change. It’s been 50 years because the opening of the primary paved highway by the badlands connecting Baja’s north and south; 30 years since I drove the entire highway for the primary time; and 15 years because the surge of cartel violence, totally on the mainland and in Tijuana, that has shaken Mexicans’ religion of their leaders and saved many Individuals away.

This road-trip journal is about who and what I discovered in Baja’s outback: a brand new technology of adventurers, spurred by pandemic restlessness and outfitted with instruments and toys their mother and father in all probability by no means imagined. Usually they discover alongside hardy Bajacalifornianos whose ancestors arrived a century in the past.

Whereas many Individuals keep away, these vacationers and their guides vary deep into a stunning, lethal panorama that has remained basically unchanged for many years — aside from the half that’s completely reworked.

“The amount of cash you see on the highway!” mentioned Cruz Santiago, who has been visiting along with his spouse from Oregon since 1997. “That’s completely modified.”

Because the worst months of the pandemic, Baja vacationers have largely resumed lolling in resorts, wintering in RVs, sportfishing, becoming a member of off-road races and elevating hell in Cabo San Lucas nightclubs. Due to the enduring attraction of heat winters, lengthy seashores and stiff drinks — even within the shadow of an epidemic on a peninsula starved for water — Los Cabos tourism reached report ranges in 2022.

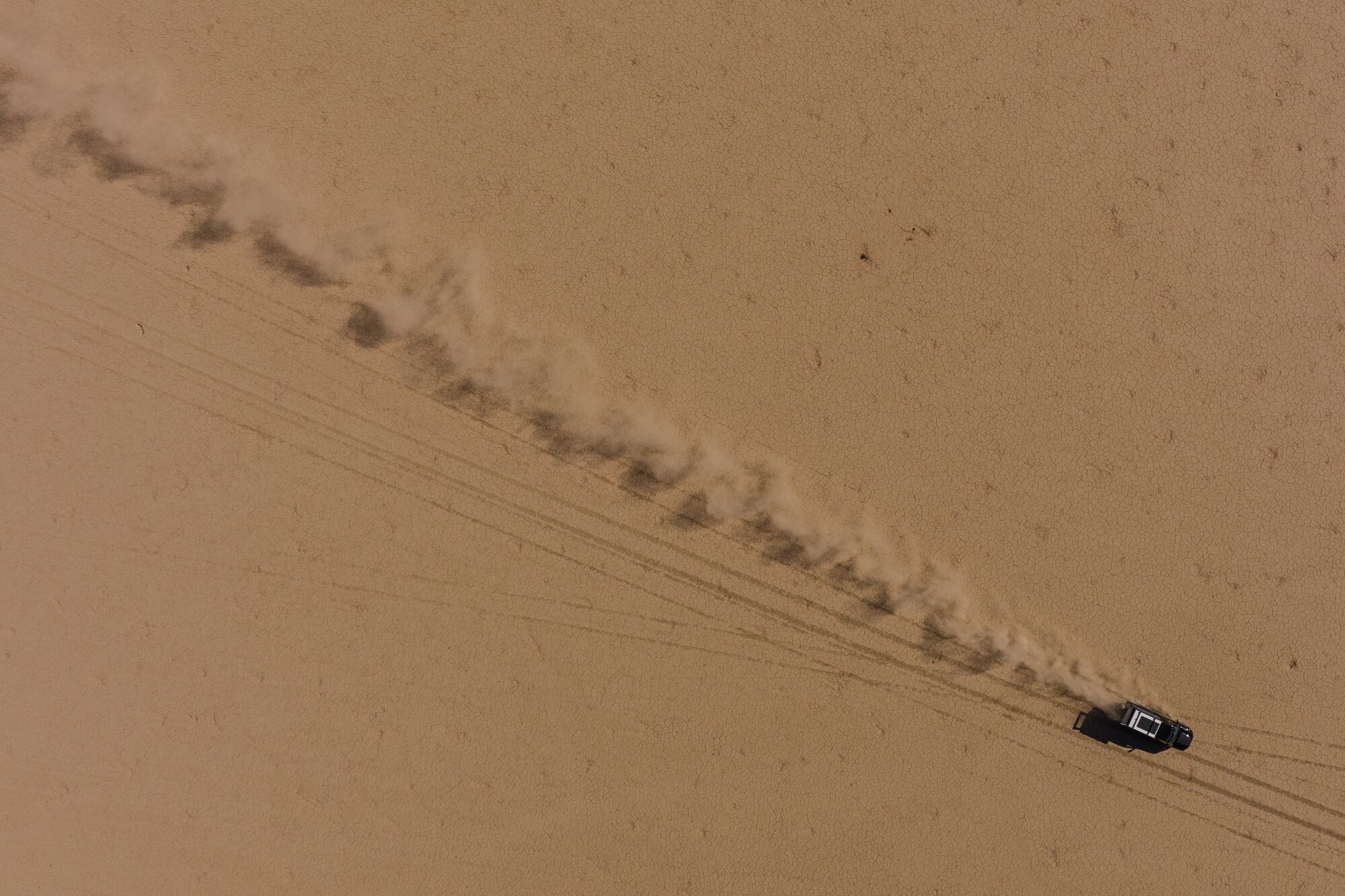

An off-roading journey alongside the Baja peninsula coast. (Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

However now many different Baja guests arrive from the north in vans, SUVs, vans and bikes rigged for tenting and backroad overlanding, a booming pastime that hardly existed a decade in the past.

Different guests steer fortified mountain bikes on the Baja Divide, a 1,673-mile dust route that was charted in 2015-16.

They’ll pinpoint cave work and surf spots by satellite tv for pc with their telephones; cozy as much as grey whales for Instagram snaps; snorkel with whale sharks close to La Paz; kite-surf at La Ventana; spurn fishing in favor of watching striped marlin assault sardines close to Magdalena Bay or mobula rays migrating off the East Cape. They ship up drones over the coast, which is longer than these of California, Oregon and Washington mixed. (And till January, when you have been courageous or silly sufficient, you might even have gone cage-diving amongst nice white sharks off Baja’s west coast —however Mexican authorities put a cease to that after a number of security scares.)

In the meantime, citing excessive crime and homicides in Tijuana, the U.S. State Division urges Individuals to rethink journey to northern Baja, to take further care within the south and to remain fully away from six different Mexican states on the mainland. (Matamoros, the place two Individuals and one Mexican have been killed in an early March kidnapping try, is in Tamaulipas state, about as removed from Tijuana as Los Angeles is from Houston.)

With all that in thoughts, I deliberate to sidestep Tijuana and spend lower than 36 hours in northern Baja. I additionally employed bilingual information Nathan Stuart, 41, who lives in Ensenada and co-founded Legends Overlanding in 2020.

Together with Instances photographer Brian van der Brug, we rented a truck from San Diego-based Topoterra, which since 2017 has specialised in off-grid automobile and tenting leases.

“Baja simply eats up time,” Stuart warned as we started to plot our itinerary. “There’s loads to see.”

The primary time, in a Toyota 4Runner

From my first journey down this highway — again in 1992, with Instances photographer Patrick Downs — I knew Stuart was proper.

On that journey we rented a Toyota 4Runner, slept in inns, relied on my sketchy Spanish, paid about $1.75 a gallon for gasoline and needed to get towed out of bother on a steep slope in Mulegé.

This time, with Stuart driving and translating, we might buckle right into a RAM 2500 truck with heated seats, 37-inch tires, a crew cab and a GoFast camper shell with a retractable tent on high. This was a $100,000 rig, rented for $239 a day.

Nearly instantly, we knew, it might be cloaked in mud and dust, like most long-haul Baja autos. Other than our freeway time, we might log about 350 miles on dust roads constructed for anglers, miners and ranchers.

Our mascot, information Nathan Stuart’s border collie Billie, enjoys the wind by the again window within the Guadalupe Valley in Baja California.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

A automobile traverses an enormous, dry lake mattress at Laguna Chapala.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

For communication we had Starlink, a subscription service that enables satellite tv for pc web entry from nearly wherever. For leisure, we might have Billie, Stuart’s border collie.

Most nights, we might camp on distant seashores and ranch land with house owners’ permission. And indubitably, we’d must improvise right here and there.

Although many Alta Californians don’t notice it, the Baja peninsula is twice the scale of Eire and is split into two states. The state of Baja California begins at Tijuana and ends about 450 miles south on the twenty eighth parallel of latitude.

Under that time, you’re in Baja California Sur, which has its personal time zone and one among Mexico’s lowest crime charges.

Whether or not you’re north or south, “Connecting with a neighborhood is what makes you protected,” Stuart mentioned.

A wheelbarrow loaded with firewood alongside the vineyards of the Bruma vineyard (open since 2016), one among greater than 150 wineries within the Guadalupe Valley.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

Mile 69: Beneath the Valle de Guadalupe

By 11 a.m. on Day 1 we have been at the hours of darkness. This was within the Guadalupe Valley, simply outdoors Ensenada.

Step-by-step, we descended into an underground room dominated by a petrified oak tree, 35 ft excessive and 200 years outdated. I assumed Physician Who would possibly materialize from one other dimension at any second. As an alternative any person popped open a bottle of wine.

This was the tasting room of the Bruma vineyard (open since 2016), one among greater than 150 wineries and dozens of lodgings within the valley now, a quantity that grew quick for a decade, then stalled throughout the pandemic.

“We give a variety of worth and symbolism to nature,” mentioned attendant Heraclio Ojeda, 29, fluent in English, Spanish and the argot of wine professionals in all places. Ojeda poured and instructed us about Bruma winemaker Lulu Martinez Ojeda and the 200-acre vineyard, which incorporates the favored Fauna restaurant.

Lengthy tables contained in the eating room of the favored Fauna restaurant, alongside the vineyards of the Bruma vineyard within the Guadalupe Valley.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

As if the valley’s rising vineyard rely weren’t sufficient, right here’s one other measure of change: Fauna’s celebrated chef, skilled in Copenhagen and New York, is Ensenada-born David Castro Hussong, a part of the identical German-Mexican household that based Hussong’s Cantina in 1892.

In a setting nothing like that raucous bar (which lives on in Ensenada), we sat at a protracted desk on Fauna’s patio and attacked the lettuce-with-mackerel starter, the broccoli with chiltepin peppers, the cabbage with chilhuacle peppers and the lamb. First meal of the journey. And the most effective.

Then it was time to hitch Freeway 1, creep by traffic-choked Ensenada and switch from luxe to rustic.

As Ensenada light within the rearview mirror and civilization started to fall away, it acquired simpler to image 1973, when Freeway 1 turned the primary paved highway to attach the peninsula’s northern and southern halves.

“The end result may very well be a contemporary paradise or a vacationer slum,” wrote Philip Fradkin of The Instances again then. Many Baja-savvy American off-roaders, surfers, anglers and conservationists, Fradkin added, “wring their fingers in despair on the considered the highway being accomplished. Mexicans sit up for such fundamentals as electrical energy, telephones, freezers, tv, contemporary meals, extra jobs and a share within the new wealth.”

A flashlight streaks alongside the picture body throughout a protracted publicity because the Milky Means offers a backdrop to a tall cardon cactus on the Baja Peninsula.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

Mile 250: Mama’s folks in El Rosario

If outback Baja’s pioneers had a royal household, Anita Grosso Espinoza, higher generally known as Mama, could be a part of it. She was one among a number of youngsters born to a Pima Indian mom and a father who got here from Italy in 1880.

Starting within the Thirties, Mama Espinoza ran a restaurant, lodging and gasoline station close to the blacktop’s finish in El Rosario, about 220 miles south of the border.

A visitor holds a framed {photograph} of Baja pioneer Anita Grosso Espinoza, higher generally known as Mama, inside her historic restaurant and lounge in El Rosario, courting to the Thirties.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

By the point the freeway opened, Mama Espinoza was well-known within the area, a bilingual spouse, mom, entrepreneur and philanthropist recognized for her lobster tacos and a ledger guide signed by Steve McQueen and James Garner.

“Dangerous roads, heavy-duty folks,” she preferred to say. “Good roads, all type of folks.”

Although Mama died in 2016 (estimated age: 105), her restaurant endures. Inside, sipping espresso beneath her portrait, I discovered Hector Espinoza, 64, a relative of Mama, retired industrial diver and former mayor of El Rosario.

Hector Espinoza, 64, a relative of Mama, sips espresso at a desk beneath images of ancestors contained in the historic restaurant and lounge in El Rosario.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

He confirmed me across the artifact room and instructed me to savor the Valle de los Cirios, simply forward.

“There’s nothing prefer it on this planet,” Espinoza mentioned.

That is the place the freeway turns away from the Pacific, coming into a world outlined by sand, boulders, spines, thorns and only-in-Mexico specimens just like the cirio tree, which is tapered like a candle and topped by a blossom of flaming yellow.

As an alternative of the Joshua bushes and saguaro cactuses of Alta California and Arizona, the valley teems with yuccas and cardon cactuses — an virtually parallel universe, virtually empty of individuals. A number of the cardons attain 60 ft, flanking the slim freeway like toll gates, making the highway look narrower than it’s.

Cardon cactus and desert fauna are framed by huge boulders close to Cataviña.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

But it surely actually is slim. For many of the subsequent 400 miles, the two-lane freeway is 20 ft huge with no shoulder and only a few turnouts. This leaves truckers and bus drivers inches to spare, even earlier than they begin excited about meandering cows and donkeys. For good cause, Bajacalifornianos urge all drivers to journey throughout daylight.

Additionally, when you move the El Rosario Pemex station heading south, it’s 200 miles to the following correct gasoline station.

“The highway could be very harmful,” Espinoza mentioned, recalling the federal government’s guarantees to widen the highway quickly after its completion. “In 50 years they’ve performed nothing.”

Mile 326: Cataviña daybreak and a mattress of coals

We camped outdoors Cataviña, about two miles off the freeway. Within the morning, like a tortoise rising from its transportable house, I appeared out from my rooftop tent as first gentle fell on the desert.

Of the 120 species of cactuses mentioned to be on the peninsula, about 118 appeared to have gathered to listen to our loud night breathing. As soon as we had espresso in us, Stuart nodded towards a spot between 20-foot-high boulders and we stepped in. Historical handprints. Darkish hashmarks.

This amazed me — till about an hour later, after we reached one other cave, this one crawling with black, pink and orange hashmarks, circles and a solar with radiating traces.

“That solar?” mentioned native information Nathan Velasco, 34. “Once you rely, there are 13 rays, and there are 13 lunar cycles. … It’s all authentic.”

On the left, shells are piled on a Bahía de Concepción seaside after harvesting in Baja California Sur. On the best, historical rock artwork decorates a cave, crawling with black, pink and orange hashmarks, circles and a solar with radiating traces close to Cataviña, Baja California.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

Locals sit at a sunny window desk at Cafe La Enramada, alongside Mexican Freeway 1 in Cataviña, Baja California.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

Velasco had joined us for lunch at his household’s Café La Enramada in Cataviña.

We talked about rock artwork and the Yuman, Cochimi, Monqui, Guaycura and Pericú individuals who lived in Baja as much as 10,000 years in the past. We additionally talked about Mama Espinoza — as a result of Velasco additionally is expounded to her.

That’s when Emily Smith and Nick Tornambe rolled up and stepped in.

Smith, 27, had come from Georgia; Tornambe, 26, from Pennsylvania. That they had been pedaling their long-haul mountain bikes for 16 days on the Baja Divide path. With luck they’d attain La Paz in a month.

“Our favourite campsite was two nights in the past, on this wash. We needed to cross the riverbed with our bicycles and it was getting nightfall,” Smith mentioned. “The moon was rising. We determined to cease. And Nick constructed this huge hearth…”

“After which we let the coals die down,” Tornambe continued, “and lined it again up, and slept on high of that. So it was like this heated mattress. Fairly good.”

Canines comply with a person carrying a trash can on a dusty lot in Cataviña, one of many solely spots to buy gasoline alongside a abandoned 200-mile stretch between correct gasoline stations.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

Mile 362: Quick automobiles and smuggled parrots in Laguna Chapala

Not far past Cataviña, the freeway reaches Laguna Chapala, a dry lake mattress that folks drove on earlier than the freeway opened. Now the highway skirts the lake, however you may nonetheless take your automobile or bike out on the flats, stomp on the gasoline and kick up mud. Some overlanders and off-roaders spend hours roaring forwards and backwards, Stuart instructed us, with drones scrambled above to seize the scene.

So in fact we needed to strive that. And we would have liked to satisfy Eugenio Grosso Peralta, 66, who has been operating a ranch, retailer and restaurant by the dry lake for many years, as his father did earlier than him, and as his son is doing now on the Nueva Chapala restaurant subsequent door.

After all Eugenio Grosso is expounded to Mama Espinoza. He’s her nephew. And his father, Arturo Grosso, brother of Mama E., was a famend highway builder and raconteur.

Standing earlier than a set of household portraits and utilizing a flyswatter as a pointer, Grosso gave us the story.

Eugenio Grosso Peralta, 66, tells his household story whereas standing in his retailer and pointing to numerous items of memorabilia along with his fly swatter in Laguna Chapala, Baja California.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

His father was dealing with punishment in 1925 for desertion from the Mexican army, Eugenio mentioned. However a normal gave him an opportunity to clear his identify. All he needed to do was scrape 250 miles of mule trails into form as a drivable dust highway between El Rosario and the mining city of El Arco to the south.

By some means, Arturo acquired it performed in a couple of yr. Later, he blazed a highway to San Felipe and fathered Eugenio when he was 64. By the point Arturo died in 1977, he had instructed numerous guests the story of the smugglers who as soon as stopped at Chapala on their method north. Parrot smugglers.

Arturo was well mannered to them, then forgot about it. Then someday on a visit to San Diego, he handed a birdcage on the sidewalk and heard two chirpy voices.

“Hey!” mentioned one among them, because the story goes. “Isn’t that Arturo Grosso from Chapala?”

Mile 475: From tall tales to grey whales at Guerrero Negro

Laguna Ojo de Liebre (a.okay.a. Scammon’s Lagoon) is about midway down the peninsula on its west coast. Each winter, a whole lot of grey whales migrate from the Arctic to those waters, wedged between huge sand dunes and even vaster salt flats, to provide beginning. The busiest months are February and March.

We boarded a panga, headed to a probable nook of the lagoon and noticed — effectively, have been seeing so little that just a few fishermen felt snug motoring over to indicate off their lobster catch. Comfort creatures.

Fishermen ply a nook of the Laguna Ojo de Liebre (a.okay.a. Scammon’s Lagoon) hoping for a catch in Guerrero Negro, Baja California Sur.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

Luckily, as soon as I’d caught on with one other panga, the joy escalated.

Tapping gently on his boat to draw cetacean consideration, this captain rapidly had us inside 30, 20, even 10 ft of calves and grownup whales as much as 40 ft lengthy. We didn’t get to the touch them, as many guests do, however we had front-row seats as they dived and breached, fluttered flukes and despatched up moist blasts of air by their blowholes.

“They’re simply so majestic, so massive, so light and so elusive,” mentioned Chris Diamond-Santiago, one other customer. “There’s one thing magical about them.”

Mile 476: My flip to drift

The closest metropolis to the lagoon is Guerrero Negro, the place few guests linger. It’s largely an organization city, constructed within the Fifties to assist the encompassing saltworks. However Carlos Couttolenc, a information who grew up on the town, has been engaged on a brand new tour based mostly on one thing he did there as a child: leaping into an evaporation pond.

As he defined, these ponds are extremely saline, just like the Useless Sea, so that you float atop the water, which is thickened by magnesium chloride. As a result of crystals type in and across the ponds, you’re surrounded by a flat, crunchy white floor. To me it appeared like Dying Valley and the Useless Sea, collectively finally.

It was the prettiest publicly accessible pond of business byproducts I’ve ever seen. I wished in.

“Sure,” mentioned Couttolenc. “You can be a superhero now. Or one thing.”

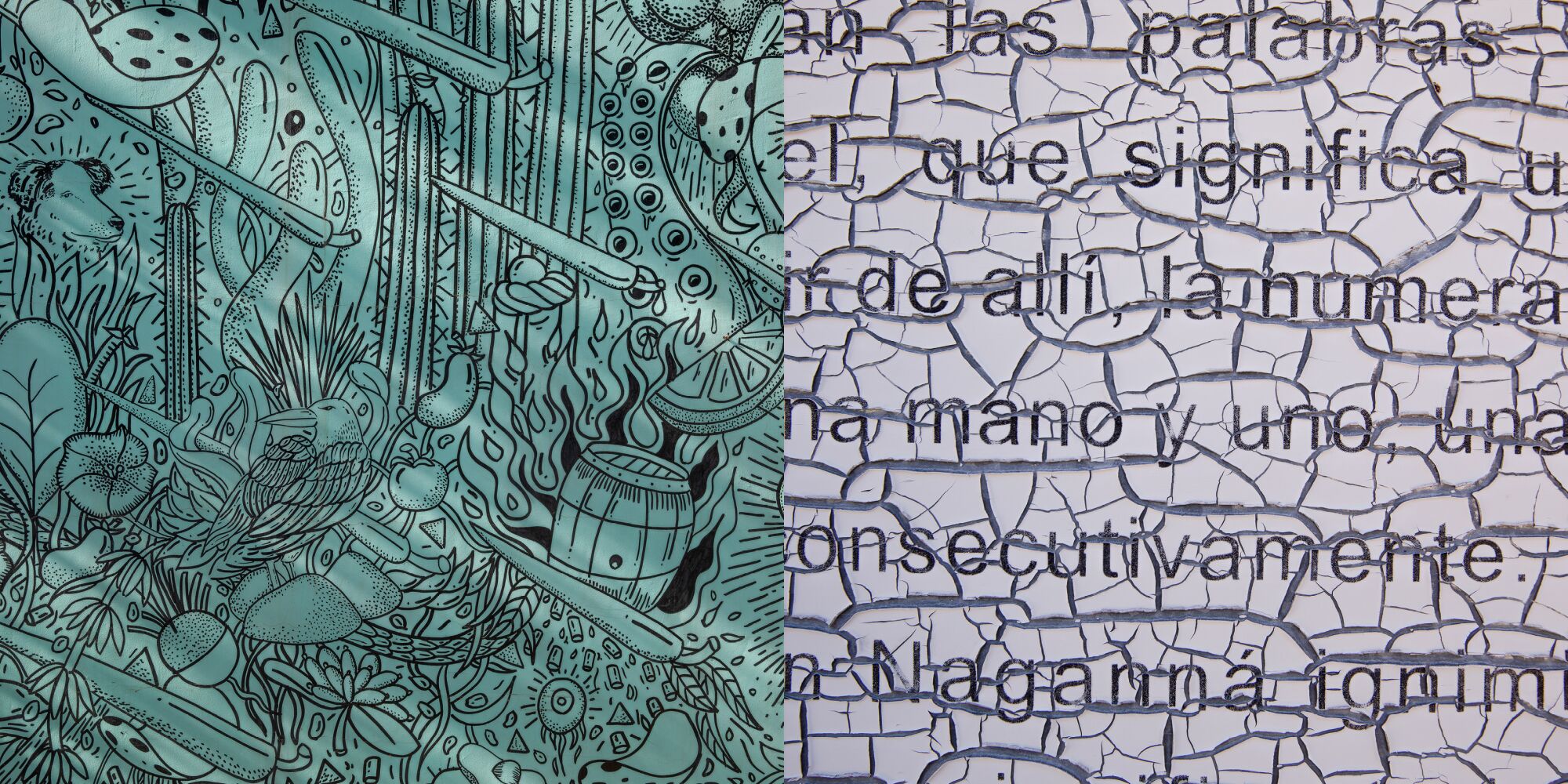

On the left, a mural on the wall outdoors the favored Fauna restaurant, alongside the vineyards of the Bruma vineyard within the Guadalupe Valley. On the best, an interpretive signal at a pure space, cracked and peeling within the desert solar close to Cataviña.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

Christopher Reynolds floats in a pond on the saline, magnesium-chloride-rich waters of the Guerrero Negro saltworks in Guerrero Negro, Baja California Sur.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

Regular guests can be supplied a straightforward method into the water and a bathe after. My entrance and exit have been extra awkward — somewhat blood, somewhat stinging. However the sensation of leaning again and floating in blue goo whereas surrounded by shiny white crystals? This was memorable.

“And it’s best to see this at sundown,” mentioned Couttolenc.

We’d lined about 440 miles now. Although we had come throughout some injury left by Hurricane Kay final September, the one disquieting second had are available an opportunity dialog by a gasoline pump.

Stuart had requested a service station attendant from Sinaloa how she’d landed in Baja.

“They killed my husband,” she mentioned.

All we may do was apologize.

Mile 530: The giants of Mesa del Carmen and the mechanic of San Ignacio

We have been about 100 miles north of San Ignacio when the six-fingered giants confronted us.

Stuart had taken us 35 miles off the blacktop and our truck was positioned on the foot of a desert outcropping known as Mesa del Carmen.

We’d already seen a full moon rise over this panorama and felt the temperature drop into the 30s. Now it was early morning. Following Stuart up a brief, steep path, van der Brug and I reached a cave, stopped and gawked.

Painted figures adorn the higher wall and ceiling of a cave at Mesa del Carmen.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

4 outsized women and men stood above us, some with six fingers, all painted on the curving rock wall. The scene additionally included a number of deer and fish painted in pink and black. To color the folks’s heads, the artist will need to have stood on scaffolding. Besides, as Stuart identified, “There’s no lumber for, like, 100 miles.”

Hmm.

We carried our unanswered inquiries to the south and east, launching right into a medley of outdated cities and seashores alongside the Gulf of California.

First up: San Ignacio, an oasis that will need to have appeared like a mirage to desert-weary adventurers within the pre-highway years. Extra palms than folks and figs on each menu. A gaggle of 18th century buildings huddled across the plaza. The inhabitants, round 1,500, hasn’t a lot modified in 50 years.

However the twenty first century has arrived. I counted three overlanding vans parked across the plaza, and three bikes outfitted for lengthy rides. On the patio of El Rancho Grande restaurant, supervisor Oscar Fischer, 28, instructed us how his great-grandfather, Frank Fischer, got here to Baja from Germany in 1910.

“He got here with a fishing ship, had a battle and abandoned,” Fischer mentioned. “He hid himself within the desert and spent two months to get right here, God is aware of consuming what.”

Paper banners grasp over the plaza outdoors the 18th century Misión San Ignacio Kadakaamán.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

A slice of fig pie from Neveria Danya within the plaza at San Ignacio.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

Fischer, who was already a talented blacksmith, realized Spanish and taught himself to be a automobile mechanic. For many years, Baja adventurers sought him out. Fischer died simply months earlier than the freeway lastly opened, however to today, half of the companies in San Ignacio appear to be run by his grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Subsequent up, an hour east of San Ignacio, was Santa Rosalía, the place the Rothschild household bankrolled a copper mine within the Eighteen Eighties, spawning a unusually Frenchified city.

Because the freeway approaches from the north, you glimpse the Gulf of California for the primary time. However earlier than the wonder can sink in, you’re surrounded by a dump and industrial zone. Then you definitely flip proper to go up town’s most important road and also you’re surrounded by wood buildings on a peninsula with treasured however few bushes. The place did the French get that wooden?

Then you definitely come to the city’s most startling constructing, which isn’t wooden. It’s the Church of Santa Barbara, a prefab construction designed in Europe and fabricated from metallic. From the within, it appears like a Quonset hut with stained-glass home windows. But it’s credited to Gustave Eiffel, who additionally designed a sure tower in Paris.

The third city in our medley was palm-shaded Mulegé, the place I wanted towing on that first Baja highway journey. This time site visitors ensnared us. Then a propane vendor stood us up. We purchased firewood as an alternative and blasted off once more, as a result of after so many citified hours, we have been prepared for the nonetheless, blue-green waters of Bahía de Concepción.

A cactus on the pebbly seaside on the Bahía de Concepción in Playa Buenaventura.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

Mile 765: The gorgeous factor we burned

Simply past Playa el Requeson, the place two dozen RVs have been lined up on a protracted sand bar with lapping waters on both facet, we turned off the freeway, feeling our method alongside the finger of land that protects the bay.

On this rugged path we met a farmer, requested his permission to camp, and pulled up at water’s edge, 12 miles off the freeway.

The solar was setting behind the glassy bay. Stuart grabbed a sun-bleached cactus skeleton and carried it to our campfire like a pallbearer approaching a gravesite.

“This would be the most stunning piece of wooden I’ve ever burned,” he mentioned.

Dawn was even higher than sundown, as a result of we acquired to see the sunshine creep up the serrated Sierra de la Giganta mountains. Finest campsite of the journey.

On the left, wind-formed ripples texture a sand dune on the shore at Laguna Ojo de Liebre (a.okay.a. Scammon’s Lagoon) in Guerrero Negro. On the best, gnarled wooden on the trunk of a 300-year-old olive tree, subsequent to the mission within the small agricultural neighborhood of San Javier.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

A sundown campfire on the seaside alongside the Baja Peninsula.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

By lunchtime, we have been within the mountains above Loreto, whispering inside a stone church that was accomplished in 1758.

Small and distant as it’s, many individuals take into account the hamlet of San Javier (inhabitants: about 40 households) the birthplace of agriculture within the Californias. Although its church isn’t as outdated because the Loreto mission (based in 1697), San Javier’s has extra charisma.

Perhaps that comes from the rugged mountains throughout, or the twisting 21-mile highway in from the freeway, or the 300-year-old olive tree outdoors, or the native households that also work the neighboring fields. In any occasion, many consultants take into account San Javier to be the best-preserved mission on the peninsula.

Finest constructing in Baja? Perhaps.

Mile 1,063: The spokesmodel at Land’s Finish

At this level, the climate had been variety to us for near per week. Now it kicked sand in our faces.

As we handed La Paz and neared the underside of the peninsula, an enormous wind blew in from the north, clouding the waters of Cabo Pulmo Nationwide Marine Park.

Our panga captain and information Oscar Cortes, 34, from Cabo Pulmo Adventures took us snorkeling at Los Frailes Bay.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

We jumped in anyway. In getting ready for the journey, I’d learn that Cabo Pulmo was a fishing stronghold till the fish practically ran out within the Nineties. That’s when native households allied themselves with conservationists and the nationwide park was created. With fishing now banned, the fish are again. The reefs are in remarkably fine condition. As is the native financial system.

“An increasing number of eating places. An increasing number of dive retailers,” mentioned dive information Oscar Cortes, 34.

As we snorkeled, sea lions swooped shut. Tons of of bigeye jack fish wrapped round me like a silver curtain. Moorish idols, bicolor parrotfish, king angelfish and Gulf grouper, noticed porcupinefish and reef cornetfish all made appearances, their scales flashing like defective pixels.

Again on the highway, we adopted the shoreline of the peninsula’s East Cape, passing miles of semi-lonely seashores and scores of fast-rising trip properties. The East Cape is filling up quick.

The close by mountains are altering too. After we hiked to a waterfall within the Rancho Ecologico Sol de Mayo, we discovered ample signage, steps reduce within the rock and information ropes — the primary I’d seen in about 900 miles.

On the left, a person stands on the fringe of a pure pool and waterfall on the Rancho Ecologico Sol de Mayo within the Sierra La Laguna mountains in Santiago. On the best, a surfer walks up the seaside after an East Cape surf close to La Fortuna, north of San Jose del Cabo.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

Heading up the vacationer hall to Cabo San Lucas, I remembered driving the identical stretch of highway 31 years earlier than.

Again then, I used to be amazed that in 20 years San Lucas had grown from a fishing village of fewer than 5,000 residents to about 20,000.

Now the cities of San Lucas and San Jose have successfully merged into the vacation spot we name Los Cabos, and their inhabitants has surpassed 350,000. Los Cabos acquired 3.3 million guests final yr, the overwhelming majority by air.

Cruise ships and yachts name every day in fall and winter. Early final yr the typical every day resort price in Los Cabos hit $455, the very best in Mexico, and the resorts hold coming. A swishy 4 Seasons is due in 2023, a swishier Aman in 2024.

An angler baits his hook as he fishes waist deep in Bahía de Concepción in Playa Buenaventura.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)

Now we had accomplished 99% of our mission trouble-free. Besides that again in Ensenada, Stuart’s house had been burglarized. And at a Rosarito Seaside resort, a 33-year-old public defender named Elliot Blair would die the following morning from head accidents that stay unexplained. In the meantime in Alta California, six mass shootings have been about to occur within the subsequent two weeks.

“Is it protected wherever you go nowadays?,” Brandon Thomason of Topoterra had requested just a few weeks earlier than, renting us the truck. “You possibly can at all times be on the unsuitable place on the proper time.”

We parked on the Cabo San Lucas marina, boarded a tour boat (not simply glass-bottomed however fully see-through) and joined dozens of vessels jostling for place. A hostess in spokesmodel make-up rose with a microphone to learn robotically from a bilingual script.

We’d reached Land’s Finish, the peninsula’s iconic pure rock arch, simply in time for sundown. The pelicans swooped in golden gentle. Waves crashed towards the rocks.

“That is the top of the Baja California peninsula,” learn the hostess from her script. “Or it’s the start.”

A ship is framed by the Arch of Cabo San Lucas, a granitic rock formation on the southern finish of Cabo San Lucas, marking the top of the Baja peninsula.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Instances)