A hunt for fungi might bring this orchid back from the brink

If you happen to ever come throughout a Cooper’s black orchid within the wild, you in all probability would mistake it for a stick — or maybe an odd potato if you happen to dig just a little beneath it. Not like many others of its form, this delicate flower is devoid of lush inexperienced leaves and flashy petals. Its stem lies on the ground of New Zealand’s broadleaf forests for many of the 12 months, solely popping up throughout the summer season months to blossom with pendulous brown and white blooms. And quite than rising a tangle of roots, the orchid sprouts a pale brown tuber.

However the possibilities of encountering a Cooper’s black orchid (Gastrodia cooperae) are getting slimmer. Fewer than 250 grownup vegetation have been discovered since botanist Carlos Lehnebach recognized the species in 2016, they usually dwell in solely three websites throughout New Zealand. To make issues worse, feral pigs, rabbits and different animals wish to nosh on the tubers. And the forests the place the orchid grows are being cleared for farmland (SN: 12/21/20). In 2018, New Zealand’s Division of Conservation categorised the orchid as nationally vital, emphasizing its excessive threat of extinction.

On the Lions Ōtari Plant Conservation Laboratory in Wellington — a part of the nation’s solely botanical backyard targeted on native vegetation — Lehnebach and colleagues are working to carry Cooper’s black orchid again from the brink (SN: 9/6/18).

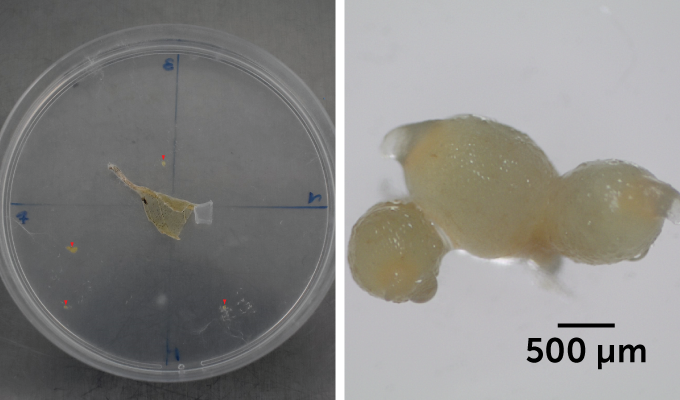

From one of many lab’s three fridge-sized incubators, conservationist Jennifer Alderton-Moss pulls out dozens of petri dishes containing the orchids’ speck-sized seeds and root-emanating tubers.

The researchers dissect the roots underneath a microscope to search for fungi that might assist the seeds germinate. Early in life, most orchids depend on fungi for important vitamins and minerals. To preserve Cooper’s black orchids, the workforce must determine precisely which fungal species provides the plant with vitamins. DNA testing helps the workforce rule out recognized orchid pathogens. Potential candidates are then extracted from roots and grown on petri dishes. As soon as they’re mature sufficient, fungi get paired up with seeds on one other dish.

“We’re working with a uncommon species, so we are able to’t simply [take] a whole lot of seeds,” says conservationist Karin van der Walt. The workforce first examined its strategies on Gastrodia sesamoides, a typical orchid that additionally grows tubers. “If we get it incorrect, no less than we’re not inflicting extinction,” she says.

It took the researchers a couple of 12 months of trial-and-error to seek out the proper germination methodology for Cooper’s black orchid. As soon as they did, they needed to wait one other two to 4 months for the seeds to sprout.

Alderton-Moss removes a dish from a resealable bag and factors out a fungus, an orchid leaf for the fungus to feed on and some seeds which have now developed into mild brown tuberlike grains. Cooper’s black orchid could have lastly discovered its excellent match in Resinicium bicolor.

Generally generally known as white-rot fungus, R. bicolor is a scourge on Douglas fir timber — a farmed nonnative tree in New Zealand — however appears to offer Cooper’s black orchid seeds with the vitamins and minerals they should germinate. The subsequent step is to develop Cooper’s black orchid vegetation from seedlings. That may reveal whether or not the fungus that helps seeds germinate is identical one which sustains the grownup plant.

Within the meantime, seeds and fungi are saved in a cold slumber in one of many lab’s sterile rooms. Seeds are saved inside an incubator at –18° Celsius, whereas fungi are saved inside a cryogenic container with liquid nitrogen at –200° C. “If we lose [the orchid entirely], we now have seeds banked within the lab,” van der Walt says. “We will no less than develop them again — we all know we are able to get that far.”

To check the viability of banked seeds and fungi, the workforce plans to thaw them at quarterly intervals to see how a lot they’ll develop.

Finally, researchers need to seed wild areas with this plant-fungi pair to spice up the inhabitants — with out all of the lab steps. Although there are nonetheless different elements to work out to make wild progress a actuality, the lab approach is “a robust method to stop extinction,” van der Walt says, not just for the Cooper’s black orchid however different endangered species, too.